Lots of algal crust to come, but first a few updates from The Nature Library.

It can currently be found at The Rockfield Centre, Oban as part of The Argyll Hope Spot exhibition, and soon makes its way to Ullapool with Glacial Narratives following its time at Patriothall, Edinburgh.

As part of the Argyll Hope Spot exhibition, I’m excited to be hosting a writing and bookmaking workshop at The Rockfield Centre on Wednesday 9 April.

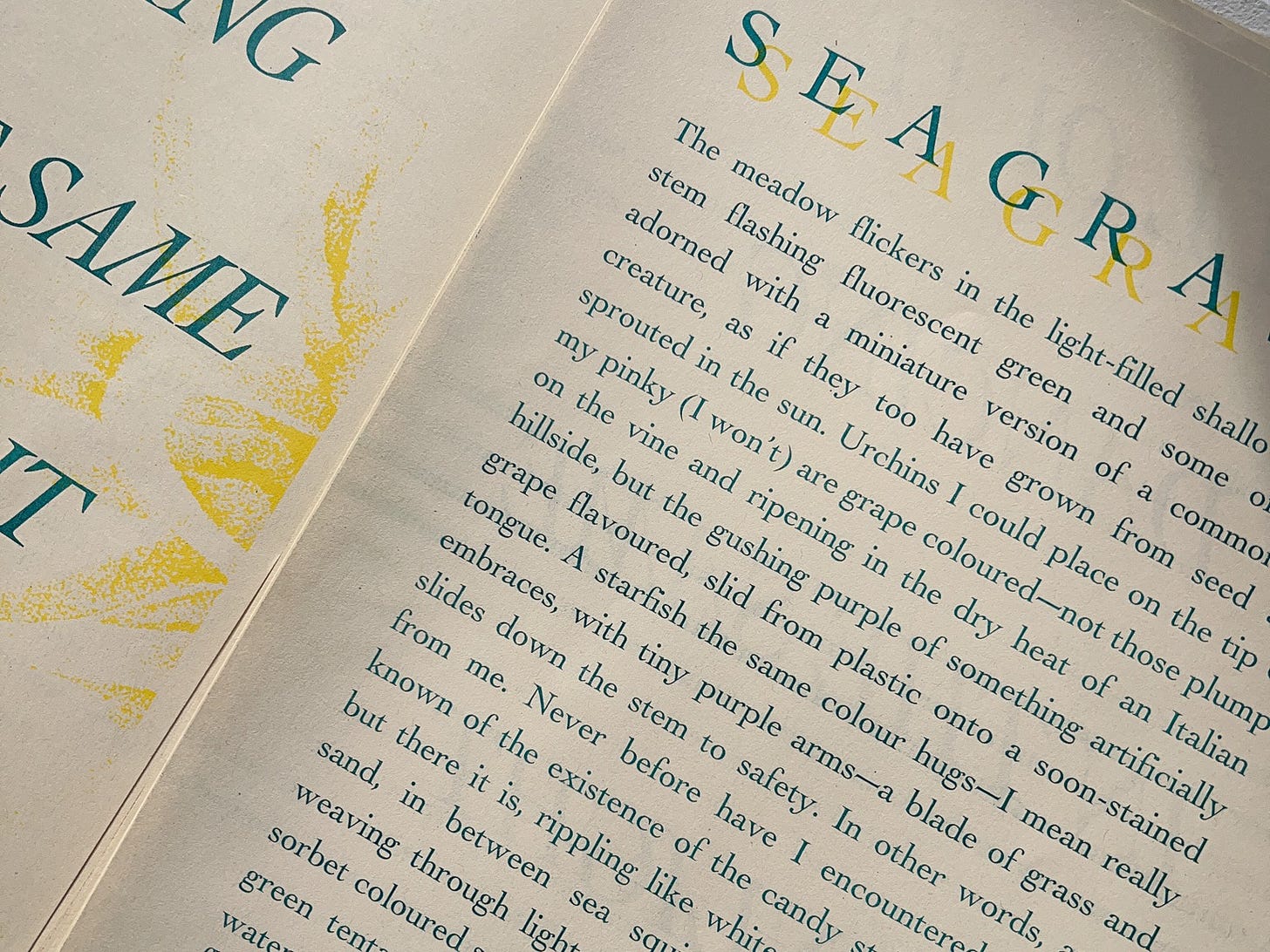

Seagrass, a new limited edition riso print, is available to buy in The Nature Library online shop, The Rockfield Centre and the library’s location in Irvine.

The next Mend and Repair session at the library, just in time for spring cleans, takes place on Sunday 30 March from 2-4pm.

There are a lot of parallels between care for the natural world and care for communities. Public libraries are built and nourished by feminist principles, so I’m extremely excited to be contributing to Feminist Librarianship (Facet, 2026), edited by Kirsten MacQuarrie.

The Nature Library is open at 122B Montgomery Street, Irvine on Sundays from 10am - 4pm, or by appointment by emailing thenaturelib@gmail.com

I enjoyed a crustiness forming on the painting, lumps and bumps, warts that came from re-working and changing the painting, what Peter Lanyon called his ‘barnacles’, which he cultivated on a painting’s surface. I think of these fighting and challenging the image, as if the painting was painted on a wall that was scored with time’s accretions.

Andrew Cranston

Edging along the gallery walls, I keep saying to

(who brought this exhibition to my attention) that these colours aren’t the colours I expected to see, but I don’t know what it was I expected. We comment on how fitting it all is for this time of year, when every lick of sunlight is savoured like a thimble of ice cold water after a marathon. We sink with ease into the florals (for spring), embraced by walls of pastel blue and yellow, mint green, turquoise, deep purple, coalescing to form a meadow which seems to breathe a collective sigh of relief into the room.There’s one colour which crops up in all the paintings I’m drawn to the most: a pink that rolls into purple or orange depending on where it’s found, eating up the spectrum like a bee rolling around in the first bloom of the year. In some paintings the pink glows as though backlit by sun in shallow water, while in others it regresses into shadowy crevices. It spreads like a spilled thing thick and crusting. Sugar taken too far in the pan. In Andrew Cranston’s Fairly Liquid, petals of pink flutter from behind a cracked surface layer. Tessa’s Garden by Hayley Barker is lush with pink and purple wildflowers taller than I am, as though I could walk right into them like a portal to a secret garden. Shota Nakamura’s Melchee is an immersion of rosy hues, a pink vessel for the silken sea that quivers gold in the middle of it all. I’m clenching my fists between words as I write this, the desire to claw my hands into it apparently not quite satiated.

I know this pink. I’ve clawed at it before.

Coralline algae is a red seaweed, part of the Rhodophyta phylum (Greek, meaning rose plant). Unlike the kelp that piles up on beaches in heaps of fleshy tangle, coralline algae cloaks its body in a calcareous shell and comes in two forms — there’s the branching, ‘articulated’ corallines such as maerl, each piece a tiny sculpture, amassing in clusters on the seafloor to form beds of calcified twiglets. They’d look like the bones of a creature long dead were it not for their magenta glow, alive and feeding off the sun. Then there’s the nonbranching, ‘unarticulated’ corallines, spreading a slick pinkish-purple crust over rocky reefs and topping the shells of limpets with a pretty pink glaze, turning them into playpiece biscuits. Collectively, these encrusting coralline algae are known as ‘pink paint’.

In letters to Dorothy Freeman, Rachel Carson wrote euphorically about the world revealed beneath the pink paint’s hard crust,

The other especially choice thing (and I really got excited about this, because I didn’t know it at all and have never seen any report of it) was the discovery that, where the pink crust of the corallines over the rock has become thick and heavy enough that the pieces can be chipped off, there is a whole community of creatures living in and under it. … The whole algal crust is riddled with the borings of things that have made a home in it, and with winding tunnels going off in all directions; sometimes one of those very tiny crustaceans that has a single, glowing eye would come up out of the darkness of such a tunnel, always reminding me of a miner with a headlamp. Well, you see I had a good time.

Always, Rachel: the Letters of Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman 1952-1964

Next to Melchsee, Shota Nakamura speaks of seeing light in the marks of Pierre Bonnard’s paintings (which all of the artists are responding to). Nakamura sees “light in [Bonnard’s] marks … I see and hear the sounds of light, which seem to shiver in his paintings”. It reminds me André Breton on coral (which as you might guess from their name, coralline algae were once thought to be), describing their beauty as “convulsive … like the feeling of a feathery wind brushing across my temples to produce a real shiver”. Senses layer on top of each other throughout the exhibition; pink and purples are sweet like sugar, while red spots clang against otherwise tender scenes. Sunlight sprinkles over water like sand onto tinfoil. Salty scallop shells scatter around the room, on bathtub rims and bedside tables and swimming in Lorna Robertson’s Half-remembered names and faces, convulsing with colour like one of Breton’s coral reefs.

Seeing maerl, my sense of sight blends into sound and taste, partly because it makes me want to stuff my mouth with strawberry Millions but also because my developing love for coralline algae has also led to affinities for particular words. Coralline, for one. Calcareous. Something about the click of the ‘c’ and the ‘l’ together. I suppose click, then, would count too. These are words that click for me. Fragments of language interlocking to form something that feels whole on the tongue. I don’t know why — maybe it’s obvious, maybe a linguist would read this and say ‘well, yes, you and everyone else’. Maybe it’s like saying ‘I just love the way light sparkles on a calm sea, I can’t explain it!’. I don’t know if the pink paint inside Ingleby attracts me because of a correlation with corallines, or if there’s a common ancestor to both of these pink paints a little deeper in my psyche. I don’t know, I don’t particularly care (that’s a lie, I clearly do). In any case, isn’t it incredible that our souls seem to play matchmaker with the rest of the world? As though there’s too much beauty to connect with all of it. We’d be unable to get out of bed each day, paralysed by the way the sunrise clinks off the rim of the milk bottle, or turns kettle steam to pink mist, or slides along countertops to turn yesterday’s crumbs into nuggets of gold. Not every song can make our heart skip a beat. Everyone is capable of love but no one is capable of loving everyone. We are but small animals. And yet.

My friend and brilliant artist Laura McGlinchey might be even more obsessed with crust than I am, and incidentally introduced me to Andrew Cranston’s work by taking me to his exhibition in Paris where, once we finally found the gallery (by following a man and his dog into the unmarked building we had to hope it was in; public access to art a subject for another day), I gazed at spectres of Ailsa Craig painted onto book covers. We floated out of there, imagining the Sliding Doors branch of our lives had we given up on finding it, as we almost did.

In Laura’s zine Crust: An Archive, discarded chunks of paint from her studio are presented like isolated specimens, as though once alive. A kind of cabinet of crusty curiosities. The book is comprised of four categories — Disks, Chunks, Crustaceans, Crumbs and Flakes (the word crustaceous literally meaning ‘having a crust or shell’). In 2018, for the Suttie Arts Space at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, she exhibited a Paint Rock Scanner inspired by the first MRI machine; visitors could choose a chunk of paint crust and be shown interpretations of the colours inside, inviting people into their own versions of Carson’s microscopic world.

The universe unfolds infinitely inward as well as out. The pink paint of Andrew Cranston, Shota Nakamura, Hayley Barker and Laura McGlinchey all have, or at least suggest, layers of life beneath them, and suggestion is as real as any material existence. The presence of a crust is really the presence of what’s underneath. I want to shrink myself into the channels of the pink paint — both the pigmented and the algal — worming my way into the depths of all the real life I can’t see from here. And there again is the urge to claw. Pick at Cranston’s barnacles to see if those glowing crustaceans are where the light of Fairly Liquid is coming from.

I apologise in advance to whoever lives in the next pebbledash house I walk by.

Making our way to Waverley station, through the purple crocuses of Princes St Gardens, Roxani asked her signature questions that always permeate the surface layer. One was simply (though we know by now that it’s not simple), how did the exhibition make me feel? Though I’ve been rambling on about it now for some time, I find it difficult to describe how something makes me feel. It just did. But there’s always more and I’m always grateful for being encouraged to dig. So, the feeling I get when confronted with any kind of beauty, whether hung on gallery walls or enrobing the rocks at low tide, is that it makes the world bigger. Or, more specifically, it grows for me without shrinking for anyone else, a kind of growth Jonathon Porritt writes about in Seeing Green which emphasises not “tangible, quantitative possessions, but [deals] equally with growth in personal and human resources”, not “constrained by the finite physical limits of our planet.”

The value of art at this moment in time also came up. How it feels to try to make it, or to pay attention to it, or encourage others to pay attention to it, while much of the world burns; literally, in some cases. We know it matters, but does it? Yes, of course. But does it?

The Trump administration seeks to close over thirty National Park offices, dismantle Diversity, Equity and Inclusion programmes and, as of today, eliminate the Institute of Museum and Library Services. In the UK, welfare support goes down while military funding goes up. Meanwhile I post a book of California wildflowers on Instagram, its chapters arranged by colour (Rose to Purplish-Red or Brown, White to Pale Cream or Pale Pink or Greenish, Bluish). Ridiculous. Not the worst possible thing I could be doing, but ridiculous.

Is picking up a book or looking at a painting or talking about them with a friend going to make the world a better place? Not alone, no. But when you scrape back all the layers of history, “time’s accretions”, it always reveals the same things, the same hues of humanity, the same old light-against-dark stories. Every time someone chooses to give their attention to a book, or a painting, or a friend, it’s attention — therefore, power — away from those who can only gain power by taking it away from others. We establish that thing as something that matters to us. As Rachel Carson says, “The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction”. Everyone knows this story. And while I don’t want to give some current world leaders (leading us towards what?) the honour of being compared to crust, I am reminded of a line from Ben Nicolson in, I think, Margaret Gardiner’s Barbara Hepworth: A Memoir:

There is at least this that all the badness in humanity is coming to the surface and can be tackled openly

Not all crusts are horrors — hopefully that’s clear — but I do like the idea of these ones as a surface to be clawed, scoured, each of us with our own little corner to pick at. So Roxani and I agreed that if there was a time to spend our days thinking about care, community, attention, light, beauty, love, it’s now. It’s obvious. And it would annoy the oligarchy, and I think that matters.

Heading home filled with pink paint (and a splash of pink wine) I felt richer, life itself more pigmented, another layer added. I looked back at my photos of Andrew Cranston’s paintings in those ornate Parisian rooms and am pleased to be reminded of my favourite of them all:

song / book

Continuing the theme but with less barnacles, Light by Eva Figes, imagining a day in the life of the Monet family, is paired with My Slumbering Heart by Rilo Kiley.

And we'd better hurry up

And it's late and the sun keeps on shooting through pine trees

…

My mom, she cried about money and time

And how she felt older

…

My dad played in the bar

And I wondered if I looked like himMy Slumbering Heart, Rilo Kiley

He strolled along the grass verge, saying his habitual goodbye to shrubs and trees now glowing in a final incandescence he had not captured, not yet. He had been wrong to think of light as a veil, playful and shimmering, between him and solid things. That was how a young man saw things, in midsummer, and at midday. But now, especially in the early morning and in the evening, he saw it for the illusion it was.

Light, Eva Figes

Currently reading: The Years, Annie Ernaux

See: Wings of a Butterfly at Ingleby Gallery, until 19 April

Read: Poll finds 40% of Britons haven’t read a book in the past year

Write: Regenerative Words: The Creative Act of Writing, a workshop by Annie Lord with Just Write

Read: A living seabed: monitoring maerl in the South Arran MPA

See: Forbidden Territories: 100 Years of Surreal Landscapes at the Hepworth Wakefield, on until April 21

So pleased to revisit this experience through your words!