The rain rushing down the window warps the lamppost outside, prying the metal open like the eye of a needle. The wind is pounding the glass and I feel it rushing through the hole at speed, tumbling out the other side, making it shake with the force of it all. I’ve been thinking a lot about movement lately and have to remind myself that outside, the post remains solid and unyielding.

A few updates from The Nature Library since the last post first, then a bit about rhythm and language and the way things move, and if you make it to the end there’s not one but two song/book pairings. Annie Ernaux gets two.

— The library is now closed for the holidays*, opening back up in early January and off to some new locations in 2025. I’ll talk more about the year the library’s had later, but for now I’ll just say with every ounce of my being, thank you for continuing to support it.

— A huge thank you to science artist Vojta Hýbl, who came to the library in November to host a drawing workshop on the beauty and the stories of rocks. inspired by Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain.

— Later that month, Jane Smith and Renuka Ramanujam joined me for Book Week Scotland to share our experiences as snorkelling artists-in-residence at the Argyll Hope Spot and to talk about hope, art, books and Scotland’s seas.

— On December 7, Kirsten MacQuarrie and Gerry Cambridge were in conversation to celebrate the launch of Kirsten’s debut book, Remember the Rowan, inspired by the life of Kathleen Raine and offering a feminist retelling of a relationship behind one of Scotland’s best known nature writers. You can listen to their conversation here.

*It can open by appointment during this funny few weeks, just email thenaturelib@gmail.com

Up to date hours for The Nature Library can always be found on the website, www.thenaturelibray.com

body language

[These moments] come to me most often, as I have indicated, waking out of outdoors sleep, gazing tranced at the running of water and listening to its song, and most of all after hours of steady walking, with the long rhythm of motion sustained until motion is felt, not merely known by the brain, as the ‘still centre’ of being. In some such way I suppose the controlled breathing of the Yogi must operate. Walking thus, hour after hour, the senses keyed, one walks the flesh transparent. But no metaphor, transparent, or light as air is adequate. The body is not made negligible, but paramount. Flesh is not annihilated but fulfilled. One is not bodiless, but essential body.

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain

I started thinking about movement and language back in summer, in the middle of Edinburgh’s festival season. Creative Scotland had just announced the closure of their Open Fund for Individuals; odd timing since the book festival alone was a showcase of success stories from that very fund, from Jen Stout’s Night Train to Odesa (which recently picked up First Book of the Year at Scotland’s National Book Awards) and Amy Liptrot’s The Outrun, premiering both screen and stage adaptations. So the ripple effects of one individual’s individual fund is quantifiable, and in some cases could be considered quite a wave. What ripples out from each person who watches a film, sees a play, reads a book, is harder to trace. That’s expected. It’s expected to be unable to explain that which pertains to how we feel, so it’s frustrating when the unexplainable is forced to prove its worth lest it be taken away. It’s a good thing love doesn’t have to be defined and quantified to retain its value or we’d all be fucked. But I’m not saying anything new here. Art is important! It doesn’t matter how or why, it just is!

This is what I came away from the festival thinking. Groundbreaking.

In particular, I thought of the value of accessing different forms of art. We’re all walking around experiencing life in different kinds of ways, so we just keep making stuff in the hope that something, somewhere, sticks. There are endless ways of feeding the soul the way we feed the body and as arts and culture continue to face cuts, I try to imagine what a world without them would look like, and how long it would take for one malnourishment to begin eating away at the rest of the body and mind, how its people would feel, and if those in charge of which parts of society are nurtured and valued have also looked at these futures and thought “That looks fine. That’s the world I want to create.”

I love books. I love books so much that one day while reading on the couch I thought to myself ‘I wish this could be my job’, so I started a small library and will continue that library every day until somebody says “Okay Christina, enough now”, and surely someday, surely soon, that day will come. But after numerous trips from Troon to Edinburgh International Book Festival, walking the stretch between Central and Queen Street enough times to have contributed to Glasgow’s fossil record, for my final night in the capital I bought a ticket for Crystal Pite’s Assembly Hall, a show of contemporary dance (which was performed at Festival Theatre. How long it took me to piece this information together is unimportant).

Sitting down in the hum of that dark theatre felt like entering another realm; whether it felt more like a returning to reality or an escaping from it I don’t know, but it was a palpable shift after being so immersed in books. People talking about books. Books they’d written or books they were writing. Books we loved, the covers of books, the buying and curating of books. I was having such a good time with people talking about books that I momentarily forgot the impact of saying nothing at all. Admittedly, Assembly Hall might not be the best example here since it’s accompanied by voiceovers and so not entirely free of speech, but on the other hand, that proved the point, if there was one, even more. Language inhabited the dancers’ bodies as their limbs were stretching and folding and slinking around each other, responding to the cue of music or to the spoken word or to the touch of another person. They were saying everything we were saying in between events at the book festival, every rant and rave about funding and the arts and community and the spaces they build and fill and storytelling and the beauty of the mundane, the extraordinary everyday, and the simmering splendour of people even, or especially, when they seem to be doing nothing at all, and what all those little not-quite-nothings become, together. As I watched, all I could think was the body, the body, the body.

Not everyone reacts this way to dance, though Pite does believe that there’s something humans inherently find appealing in synchronicity. One of her previous works, Emergence, was inspired by the structure of a ballet company and how that structure is mirrored in the natural world, looking to insect colonies such as beehives where many work as one:

Rather than being led or dominated by a small number of individuals, decisions are group efforts. ... The bees engage in a very lively and competitive debate until opinions start to coalesce. It is not a hierarchy at all. The queen does not govern.

But still, no, not everyone will feel how I feel when I watch dance. Or how the woman next to me felt anytime she let out an involuntary gasp or giggle and threw her hands up to clap, catching herself just before they touched, realising that while her body urged a response, etiquette held it back. People who respond to the body need to see the body. People who want to laugh need to be told jokes by people who want to tell them. People who have a story need to meet those who want to hear it. The same painting might make one person laugh and another cry,. These are often but not always the same people on any given day. A variety of art is important!

I walked out of Festival Theatre rethinking my entire practice, my whole belief system. “That’s it. It’s about bodies. The body, the moving body”. But wait, a week later I leave another show with tears still in my eyes and think “Oh wait, that’s it. Music is it.” A week before, I was getting goosebumps at the festival just being told the premise of a book that doesn’t even exist yet. Oh wait. Oh wait. It’s as though we need it all.

At the launch of his latest novel Small Rain at Portobello Bookshop,

spoke about the physicality of a sentence as though it’s a kinetic power in and of itself, existing outwith language, working words like muscles until the movement flows through the body and rolls off the tongue. “The humming urgency” he called it, these linguistic pushes and pulls tugging and releasing. Not only did he speak with an earnestness that would be striking enough on the page let alone being spoken before you, filling the very air you’re breathing, but he spoke about it with such grace I immediately wanted to see those sentences translated into dance. With a background in opera and poetry it’s no wonder that the rhythm of language matters to Greenwell, and maybe literature and the performing arts should coalesce more often. (Another chance here to lament being unable to take music at school because I chose art, and it was one or the other, god forbid we spend too much time expressing ourselves). Rhythm exists without language and language exists without rhythm and there are many things written and spoken with no rhythm at all and they matter all the same, but, and I’m mixing metaphors here, but, I’d suggest that writing without rhythm is like cooking without salt.He was holding one of her hands in both of his, or trying to; she kept twisting her hand free and he kept taking it again, stroking it, letting go only long enough to push her hair out of her face.

Small Rain, Garth Greenwell

The comma, for when I’m still thinking, not done yet. I love them. They’re a hand stroking the sentence along, the stream of consciousness, thoughts slipping off each other. “Keep going”, they say. The full stop squeezes the hand, maybe even lets it go. The semicolon is one arm linking another; we go well together, don’t you think? And the em dash — always there for you — taking the emphasis, that sentence within a sentence, filling it up like one more breath right at the top, holding it.

Benesh notation, or choreology, was created by Joan and Rudolf Benesh in the late 1940s as an “aesthetic and scientific study of all forms of human movement” — a language of the body, represented through a series of symbols to find a correspondence between sound, meaning and movement understood and shared by others regardless of the one spoken by the tongue.

Since no essay is complete without some etymology, here’s correspondence. Early 15th century meaning “resemblance, harmony, agreement”, from Medieval Latin correspondentia, a harmony between com, “together, with (each other)” and respondere, “to answer”. There’s nothing in the word correspondence which makes it inherently good or necessary (which is not ever to say that only good is necessary), but it does bring good things to mind, and if I look at its antonyms — clash, disagreement, discord — then yes, an idea is formed. A truth, even, at least in our language, that correspondence, harmony, agreement, is something to be desired. And so things which enable and encourage correspondence — storytelling being my example here, whether through the language of the body or the mind, but there are many — can be understood as good. And so taking away points of contact between people, places where we can correspond, find harmony, you could say, is bad.

In 2014 when I was working for Scottish Ballet, the company presented a double bill of contemporary dance and I recall achingly long meetings trying to come up with a name for it. The title had to bind two contrasting and unknown (to our audiences) works together. This title had to summarise both, it had to highlight both their choreography and their scores, it had to have an edge while also appealing to the masses. If you can think of one, let us know.

One of these works was by the English choreographer Christopher Bruce. Titled Ten Poems, it was created after Bruce stumbled upon a vinyl record of Richard Burton reading the poems of Dylan Thomas in his local music shop. Taken by the rhythm of the words as much as, if not more than, the words themselves, Bruce used Burton’s voice as the dancers’ sole accompaniment. He shaped Thomas’ poems into a physical language that could be recognised — learned — by the audience as words and themes were repeated, each step naturally falling into the next as though being spoken. There’s magic — Bruce believes and I agree — in the transience of movement or spoken words, these things that only exist in the moment. And extraordinary value, I think, in these ephemeral experiences and expressions at a time when so much of our lives is shared, stored, saved, cached.

Dance allows us to explore territories that words can’t pin down … and I think one of the beautiful things about dance is its ambiguity, is its sense of not being able to quite catch it, but it’s an embodied sense of something. Physical communication is eighty percent of the way in which we communicate, and words are twenty percent. So in a way, the question should be, why do we speak?

Wayne McGregor, Why Do We Dance?

Why do we dance? “For me, dance was about expressing myself through movement,” says choreographer Marc Brew in a conversation with Ailbhe Turley. “Drawing on the unique physicality of each performer, the work with disabled and non-disabled artists is honest, unsentimental, and recognisably human”. He recalls how he felt when he not longer fit the mould that traditional dance training put him in, and how he used that release from a restricted form of dance to find new ways of moving. Continuing to use existing, shared tools — such as synchronicity — but also giving dancers phrases of dance to translate into their own physical language.

"The force that through the green fuse drives the flower”, wrote Dylan Thomas; it’s reminiscent of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, in which she tells the story of her “first taste” of Anishinaabe, her missing language, in the word puhpowee, meaning “the force which causes mushrooms to push up from the earth overnight”. Language moves us; an untouchable force that can be danced with — sometimes the lead and sometimes the follow — but never pinned down.

Dance was a pretty central to my life growing up — from formative childhood classes and extravagant, unnecessarily stressful end of year performances (RIP Magnum) to the sticky floors of Glasgow clubs in my teens and twenties (and occasionally thirties). But while maybe not everyone sees elaborately choreographed dances while listening to music (sequel idea, The Five, Six, Seven, Eighth Sense), dance — by which I mean rhythm, I think — is undeniably significant to people and cultures across the world. If we can’t dance physically then there are other ways for our bodies to find rhythm, and that’s maybe where art, all of it, comes in. I wonder if it’s only humans who feel this way, but only briefly. To think that something can feel so instinctive, so in our bodies rhythm, and be unique to humans alone feels irrational. It doesn’t take long to think of other examples.

Birds of paradise — the young males begin practicing before they even have the feathers which make the performance the spectacle that one day it’ll be. They practice in isolation and to each other, hone their technique by watching adult males, and when the time comes, they take to the stage. The females fill the world with the best dancers.

And we know about the bees, right? Bees who use a dance — the "waggle dance” — to communicate with other bees where to find the sweetest nectar.

“But it seems a strange connection, bees and speech,” I go on. “To be so widespread, I mean. Because bees don’t actually make sounds with their mouths at all.” And I tell her about the places they do make sounds from: their wing muscles and their abdomens; and then there’s the waggle dance and the pheromones, which are also a kind of speech.

Helen Jukes, A Honeybee Heart Has Five Openings

(I recently learned about the Ayrshire Nectar Network1, a project by the Scottish Wildlife Trust creating and connecting pollen rich areas between Irvine, where The Nature Library is based, and Girvan to the south, and am now thinking of all the bees dancing around and above me.)

Forms of communication through movement, a physical language, yes. But an urge to respond to a feeling, an uncontrolled, unlearned physical need to dance to music the way a person reflexively laughs at a joke, what about that? Well, in 2019 researchers in Kyoto determined that chimpanzees dance “to some extent in the same way as humans”. By this they mean that they responded to music unprompted and unrewarded (that is, without being given any treats by an external source, but who knows what they felt internally, and if they regarded those feelings as a reward). Their “rhythmic moves suggest that the urge to dance has a prehuman origin, reaching at least as far back as the primate from which all humans and chimps descended.”2

A cockatoo was reported to bob their head to the Backstreet Boys and Queen, changing the tempo of the bop accordingly. And elephants, too. Makes sense — they’re considered to be one of the most empathic species on earth and I don’t think there’s a lot of stretching required to get from ‘empath’ to ‘dancer’ — but on further reading, the movements an elephant makes to music are considered to be those of distress or boredom. So, valuable to be aware of (and prevent, one would hope), but not the kind of dancing I’m curious about.

Elephantnose fish (elephants again — is it something to do with the trunk?) apparently use movements such as “twisting, pacing, and shimmying to ‘see’ objects by interpreting the changes to the electric field around them”3. The movements allow them to see one object from multiple perspectives, turning a 2D image into a 3D one. Again, it’s too easy to make the link between dancing as a means of experiencing the world from a different perspective. But that’s what art is, isn’t it? And is that why we’re here? To see and experience as much of life, to feel it as deeply as we can while we can?

Starlings. We’re lucky in the UK to have year round starlings, their numbers increasing in these colder months as some fly down from Scandinavia. Quite a few of these gold threaded birds have taken up residence in my neighbourhood, reminding me most mornings of their collective noun, a chattering. Every time I think I’m used to their language, a cacophony of sounds chirping and clattering outside my window, they make one which I want to call human, unbirdlike, only that’s absurd since it’s a bird who made the sound. Maybe it’s me who should be reassessing what sounds are “birdlike”. They, like humans, or perhaps we, like birds, dance. Swathes of them dance across the sky as though being gently guided by the spellbound hands of a composer, an orchestra of small bodies rising and falling on the air as one. Their murmurations glide through the sky with grace and it’s still unknown, to humans, exactly why. Each bird knows which way to move and when, seamlessly synchronising with its neighbour. One movement naturally falling into the next.

Researchers found a commonality between these species which I found interesting since I was getting to the point in writing this essay where I was wondering quite solemnly if I had a point. What linked all of these species is that they are all vocal learners. All of us can control the composition of the sounds we make, the pitch or the rhythm, the volume, the speed.

Our hearts — human, cockatoo, elephant, bee — beat within us, and when I’m thinking of how it feels to listen to a rhythmic voice or to see the body move in a way that makes me feel, while sitting still, as though I’m moving too, it’s as though my physical experience of being, these inner pulsings, are seeking their match. Like eyes locking and letting the energy of two people suddenly flow as one, life feeling a little smoother, clicking into place.

So it comes back to that feeling of being in sync, the pleasure of synchronicity Crystal Pite keeps coming back to, the fluidity from fragments that Mr Palomar, of Italo Calvino’s Mr Palomar, experiences in the company of starlings:

If he lingers for a few moments to observe the arrangement of the birds, one in relation to another, Mr. Palomar feels caught in a weft whose continuity extends, uniform and without rents, as if he, too, were part of this moving body composed of hundreds and hundreds of bodies, detached, but together forming a single object, like a cloud or a column of smoke or a jet of water – something, in other words, that even in the fluidity of its substance achieves a formal solidity of its own.

Italo Calvino, Mr Palomar

Not only do our bodies seek rhythm, but so does the earth (is the earth a body?). The term rewilding is often used to describe efforts of returning earth’s ecosystems to a state in which they can take care of themselves, with minimal or no human intervention. Allowing them to find their rhythm again. I understand what’s meant by it and broadly support the concept, but have reservations about the word choice. Earth had, for billions of years, a sequence of patterns and rhythms. A language understood by those who inhabit it. Reliable (enough) seasons allowed species like us to dance along in time with the sun and the rain and to thrive as a result. Only extraordinarily recently have we changed the tempo4. We made it wild.

Back to Garth Greenwell (“So back one climbs, to the sources”, to quote Nan Shepherd, always). Small Rain pays what he calls an “agonised attention to the body”. He told the audience that he moves his hands as he writes, finding the muscularity of the sentence. There’s something I can’t put my finger on, as though I’m feebly trying to describe something that doesn’t exist. More likely is that I just haven’t figured out how to describe it. Or is it more likely that it’s impossible to? I don’t know! I’m looking for where body language and spoken language meet, but it feels like trying to find that “connection with nature”; void from the outset. How can the mind be connected to the body if one is the other, or is the sticking point that I’m referring to each as a singular thing — a mind, a body — when it’s not that simple? When every body, every expression of feeling, though expressed through shared languages, is unique? What feels simple, which isn’t to say easy, is to feel for any and all moments where something can fall naturally into the other, whether that’s in the rhythm of words on a page or bodies onstage, or elsewhere. Paying acute — agonised — attention to language of all kinds. I wonder how that would effect what’s spoken by any human being on any given day.

Last week I saw Scottish Ballet perform The Nutcracker and thought for the nth time how sweet it is for someone to take their short time on earth and with those precious, fleeting moments, choose to say “I will sing”, “I will dance”, “I will tell you a story”. How glad I am that people dance, tell stories, build stages and place seats in front of them. It’s a very good idea, and one we’ll never tire of. That’s intelligence at play (the real stuff). We will always want more of it.

song/book

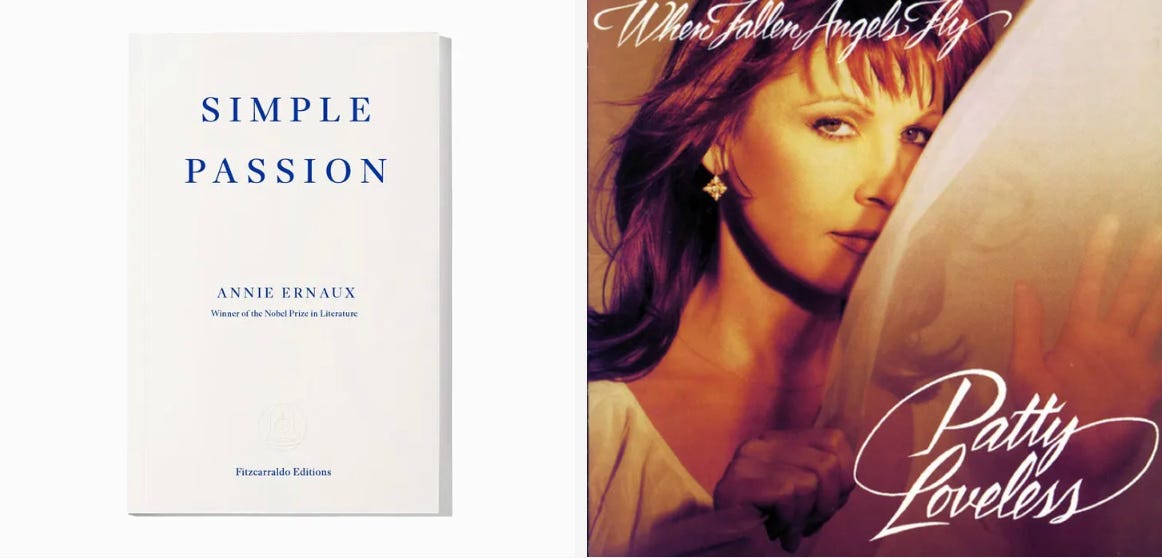

I’ve wanted to post these as a pair but have been sitting on Annie Ernaux’s Simple Passion for a while because there are a number of suitable matches, but I recently read The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie in which she mentions one of their songs being by Fiona Apple, which made me feel confident enough in one to finally make a choice for the other. Here we have Annie Ernaux’s Simple Passion with I Try to Think About Elvis by Patty Loveless, and Getting Lost with Paper Bag by Fiona Apple.

Sometimes I thought that he might spend a whole day without thinking about me for a second. I saw him get up, drink his coffee, talk, laugh, as if I didn’t exist. This discrepancy with my own obsession filled me with astonishment. How was it possible? But he himself would have been astonished to learn that he never left my head from morning to night. There was no reason to find my attitude or his more accurate. In a sense, I was luckier than he was.

Simple Passion, Annie Ernaux

Come on, Patty, get it together…

I try to think about Shakespeare, leap years

The Beatles or the Rolling Stones

I try to think about hair-do's, tattoos

Sushi bars and saxophones

I try to think about the talk shows, new clothes

But I guess I should have knownI just can't concentrate

You're all I think about these daysI Try to Think About Elvis, Patty Loveless

In a burst, the sobering up. Seeing him as a playboy – or gorby-boy! – brutal (not too much though) and hedonist (why not). Telling myself that I lost a year and money for a man who, as he leaves, asks me if he can take the open pack of Marlboros on the table. It always comes to that, at twenty or forty-eight. But what to do without a man, without life?

Getting Lost, Annie Ernaux

He said "It's all in your head,"

And I said, "So's everything" but he didn't get it

I thought he was a man but he was just a little boyHunger hurts, and I want him so bad, oh, it kills

Fiona Apple, Paper Bag

https://scottishwildlifetrust.org.uk/our-work/our-projects/ayrshire-nectar-network/

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/dec/23/cha-cha-chimp-ape-study-suggests-urge-to-dance-is-prehuman

https://www.biology.ox.ac.uk/article/boogie-wonderland-new-research-shows-elephant-fish-dance-to-see-in-3d

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/dec/16/mountain-hares-at-risk-as-winter-coats-fail-to-camouflage-in-snowless-scottish-highlands

So glad so many of your dancing words have made it into the world this year, dear Christina. More of this, please, in 2025. <3

Loved this. A real rollercoaster ride of an essay! Thank you